Law Enforcement on a Constitutional Scale

Two Border Patrol agents set off into the Arizona desert to intercept several individuals reported to have slipped through the nearby border. One tracked signs through a wash. The other searched the higher ground.

The agent in the wash soon spotted five men. They carried burlap sacks, commonly used to smuggle narcotics. Outnumbered, the agent concealed himself and radioed his partner, but got no response. At one point, the agent could no longer remain concealed and so he identified himself and ordered the group to stop.

Startled, four of them ran. The fifth man stood his ground and challenged the agent. He picked up a rock and cocked his arm, ready to throw.

Alone and threatened with serious bodily harm or worse, the agent fired a shot from his rifle. The subject wasn’t hit, but he dropped the rock and fled.

This use of force case is one of eight that U.S. Customs and Border Protection investigated, reviewed and published its conclusions about, as part of a sweeping series of reforms initiated in May 2014 to fulfill the agency’s commitment to accountability and transparency when officers and agents use force.

Enforcement law

Deadly force is authorized anytime there’s a reasonable belief a subject "poses an imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to the agent or another person," according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection policy.

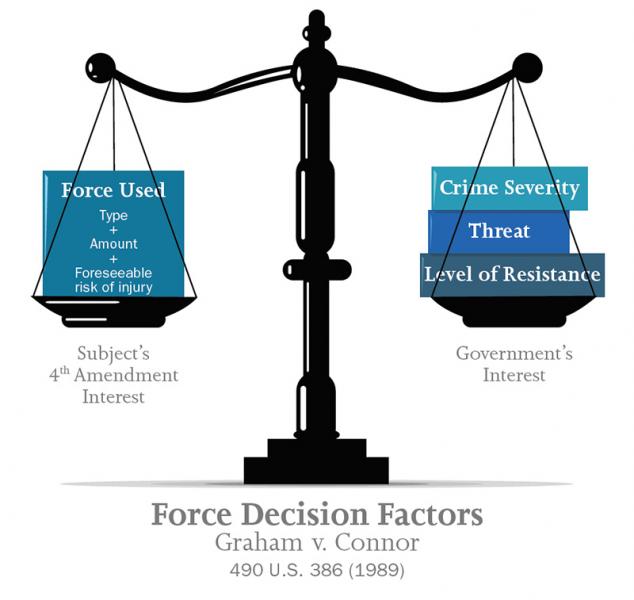

Legally, an officer’s use of force is about balance. It must be in proportion to what’s called the "totality of circumstances."

Picture a scale. The type and amount of force must not out-weigh the threat, level of resistance and severity of the crime, said Bryan Downs, an agency attorney at the Law Enforcement Safety and Compliance Directorate at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

Balancing the scale centers on balancing those factors against the risk of injury to both the officer and the subject against the need to apply some degree of force.

These essentials become the totality of circumstances that drive how an officer or agent chooses the type and amount of proportional force.

Sometimes, it’s a tough call. The Border Patrol agent in the desert facing the rock thrower had only a second to weigh those factors. An investigation concluded the agent’s action was within policy.

Incidents are tense, uncertain, rapidly evolving and many times life-threatening and begin with the way a subject responds to an officer’s commands. Most subjects comply, but some run, resist or even assault officers.

"This can be one of the most terrifying moments in an officer’s life and they have just seconds to make a decision," said Austin Skero, director of the Law Enforcement Safety and Compliance Directorate. "Meanwhile, the courts have years to debate the decision that was made."

The U.S. Supreme Court considers that burden and gives officers the benefit of the doubt.

In Graham v. Connor (1989), the court ruled that an officer will be judged by what’s considered reasonable force at the moment force is applied, not from hindsight. Use of force policy is built on such cases, said Downs.

It’s also built on the Fourth Amendment: "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated..."

"When you use deadly force, you’re basically seizing someone’s life," said Skero.

Line of duty

Across the nation, violent, targeted attacks against law enforcement officers are increasing. In 2016, 64 officers nationwide were killed by gunfire, a 56 percent increase over 2015. More officers died in the line of duty in 2016 than during any year since 2011, according to the National Law Enforcement Memorial Fund.

Border Patrol agents are among the most attacked law enforcers in the country. According to the U.S. Border Patrol, there were 7,542 assaults against agents since 2006; 1,996 rock attacks since 2010.

"There are times in law enforcement when some level of force must be used to safeguard the public or protect an officer or agent," said Matthew Klein, CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility assistant commissioner. "Whenever significant force is used, accountability and transparency are critical," he said. "The public’s trust depends upon it."

Independent reviews

That public trust was tested following a series of deadly use-of-force incidents involving CBP law enforcement personnel in 2011 and 2012. Public concern over those incidents spurred CBP to launch a comprehensive outside review of its use of force policies through the Police Executive Research Forum, an independent panel of nationally recognized leaders in law enforcement.

PERF reexamined incidents, reviewed claims from advocacy groups and then presented a number of policy, tactics and training recommendations. CBP reassessed 67 incidents reviewed by the forum. Of those, one case resulted in an indictment and another is under review by the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division.

At the request of Commissioner R. Gil Kerlikowske in 2014, the Homeland Security Advisory Council formed the Integrity Advisory Panel to recommend ways CBP can increase transparency and accountability in the ranks. Panel members visited CBP locations, interviewed employees and executives, met with union leaders and reviewed polices, practices and guidelines.

In March, the panel released a final report, which included 39 recommendations. It commended the agency’s actions to counter corruption and foster integrity. "CBP is one of the few agencies in the world that carefully studies all instances of corruption," stated the 43-page narrative that also offered a candid evaluation of the agency.

For example, the panel determined that CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility was "woefully understaffed."

It concluded that CBP needed 550 special agents to conduct timely and adequate investigations and called for an increase of 300.

To ease the shortage, ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility detailed special agents to CBP to assist with internal investigations. FBI-led task forces and the DHS inspector general’s office are also engaged.

Some of the nation’s most distinguished law enforcement experts served on the panel, which was co-chaired by former New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton and Karen Tandy, a former administrator of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

Members included Robert C. Bonner, former CBP commissioner and federal judge; John Magaw, former director of the U.S. Secret Service; former U.S. Rep. from Arizona Ron Barber; Rick Fuentes, superintendent, New Jersey State Police; Walter McNeil, past president, International Association of Chiefs of Police; Roberto Villaseñor chief of police, Tucson, Arizona; and Paul Stockton, a former assistant secretary of defense for homeland defense.

Within the agency, CBP now trains and employs officers and agents to join investigators with CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility to rapidly respond to and investigate use of force incidents. Training began in December 2014 and as of October, approximately 450 CBP law enforcers are now qualified.

As of October, these use of force incident teams traveled to 36 locations to participate with federal and local law enforcement agencies to review circumstances, gather facts and report findings to a board established by CBP to make conclusions about the incident.

Cases involving a firearm, death or serious injury that were declined for prosecution are referred to the newly formed National Use of Force Review Board, which determines "whether the actions taken were within" CBP’s use-of-force policy. The board includes senior officials from the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security, as well as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the DHS Office of Inspector General and CBP.

Based on the review, the board recommends changes in policy, training, tactics or equipment to the senior executive of the relevant operational component, deputy commissioner and ultimately to the commissioner for a final decision. So far, CBP has completed eight reviews of significant use of force incidents.

Building trust

"From the start of my tenure, addressing our agency’s use of force has been one of my top priorities," said Commissioner Kerlikowske.

Making good on his commitment to transparency and continually earning the public trust, the Commissioner reached out to representatives from Northern and Southern border groups and other non-governmental organizations to listen and discuss CBP’s commitment to accountability and outreach.

CBP leaders discussed U.S. law and use-of-force policy with officials from the government of Mexico. They formed a working group to exchange information, monitor cases, suggest preventive measures and improve training and outreach.

At the same time, CBP increased basic training by six days, focusing on the Constitution, court decisions, de-escalation techniques, officer presence and communication.

Recurrent training in less-lethal devices, conflict solutions and force policy is now required up to four times per year and simulator training is an annual requirement.

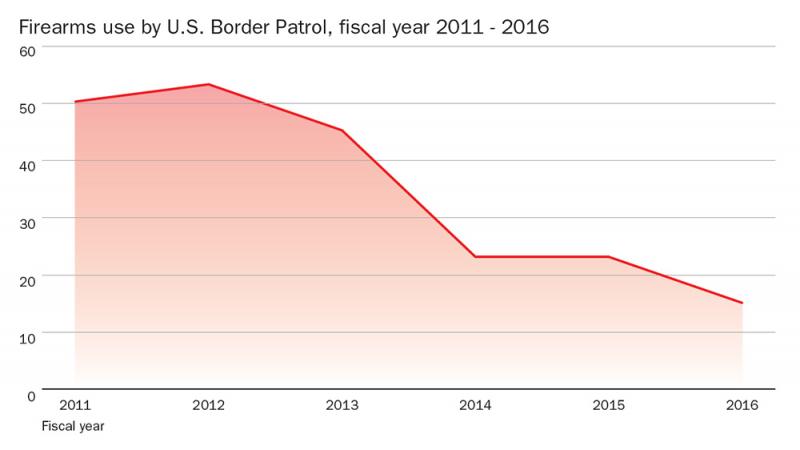

Commissioner Kerlikowske spoke about those reforms during a recent National Public Radio interview, explaining "in particular with the Border Patrol their use of firearms over the last two fiscal years is down by almost half. They have increased the length of their academy. They’ve been given a lot of less-lethal technology. And I think the most important part is that we’ve been very transparent about all of this."

Less-lethal applications have varied over the past five years but they remain substantially higher in contrast to firearms, according to statistics from CBP’s Law Enforcement Safety and Compliance Directorate.

It’s important to note that annual less-lethal figures are not the number of incidents; they’re uses-of-force, according to Director Skero. One or several uses-of-force can be counted in a single incident. For instance, if a pepper compound is fired at five assailants, that’s five uses-of-force. The CBP use of force ratio is about one-tenth of one percent of all subjects detained, or 1 in 730.

CBP established a process to release information to the public within an hour after headquarters notification. As more facts are confirmed, CBP is committed to issuing the information within the next 12 hours, preferably through a press conference.

This improved, proactive communication with the public about use-of-force incidents sets a standard in law enforcement for transparency and accountability, said Kerlikowske.

"For years we did not allow field leadership to quickly address the media," said Director Skero, who commended the Commissioner for setting the new approach.

fatal use of force incident in Sumas, Washington, in March 2015. He is joined by

Sheriff Bill Elfo, Whatcom County Sheriff’s Department, and Chief of Police Chris

Haugen, Sumas Police Department. Photo courtesy of Philip A. Dwyer,

Bellingham Herald

He cited the March 2015 news conference then Chief Border Patrol Agent Dan Harris from the Blaine Sector held after a man who attacked an agent with a chemical spray was fatally shot while trying to illegally cross the U.S. – Canada border. The 20-year-old murder suspect refused orders to stop, and as Harris explained in a press conference, "displayed erratic and threatening behavior."

"The simple act of the chief publicly acknowledging that a use-of-force incident occurred relieved much of the tension," Skero said.

Adding another step in the process of increasing accountability and transparency, CBP released the conclusions of its internal review of four cases in June and another four in November.

CBP has also committed to releasing more information about recommendations made by the national use of force review board and publishing a report of workforce discipline.

"As committed as we have become to transparency and accountability, we understand that more needs to be done to strengthen dialogue with communities and organizations," said U.S. Border Patrol Chief Mark Morgan. "We are more transparent than ever before about agents’ use of force. However, communities and organizations also should know about all we are doing to ensure migrants’ safety, the safety of communities and the safety of our agents who put themselves in harm’s way."

Air pressure, electricity and hands

Imagine yourself as a law enforcement officer. You encounter a subject who becomes combative after you ask for some identification. What would you do?

Law enforcement officers are trained to gain and maintain control through a variety of responses at CBP’s Advance Training Center in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Instruction covers everything from self-defense to a series of less-lethal devices.

"We must ensure our officers and agents have the proper use-of-force training, tactics and equipment," said Kerlikowske.

CBP law enforcers learn to counter attacks at close distances, using hand-to-hand grappling and striking techniques.

"At arm’s length, someone can pull a knife and cut you in about 0.4 of a second," said John Mansell, assistant director for less-lethal training. "Given the proximity of an assault, officers may be unable to create the time or distance needed to access their weapon or use a less-lethal option. In those encounters, they need to know how to use their hands."

Agents and officers also train to use a variety of less-than lethal responses to an attack, including an electronic control weapon, which immobilizes an assailant through an electric shock to the body, and launchers that deploy projectiles filled with a pepper or chemical compound up to 450 feet.

Agents also learn to use the collapsible straight baton and the Nighthawk, a device designed to puncture tires in the event that a dangerous, reckless driver flees from law enforcement and poses a threat to other drivers or pedestrians.

The Nighthawk came about after Senior U.S. Border Patrol Agent Luis Aguilar of the Yuma Station in Arizona was murdered in 2008. Aguilar was trying to deploy a tire deflation stick to stop a suspected smuggler fleeing to Mexico in a Hummer when the driver intentionally swerved into Aguilar. Tragically, he died at the scene.

These technologies and techniques give officers more ways to maintain control in proportion to the threat.

When Skero began his career in state and local law enforcement over 25 years ago, he remembers when a written use of force policy didn’t exist. "Things have certainly changed," he said, "and it’s good that they have."

Click here to read further: Practicing for the Unexpected