Fighting Film Thieves

Can you tell which of the DVDs in this illustration are counterfeit?

Photo illustration by James Tourtellotte

It was the summer of 2012 and Theo Fletcher, a U.S. Customs and Border Protection international trade specialist on the West Coast, was poring through data from thousands of customs seizures of counterfeit goods at the U.S. ports. Fletcher, who asked to have his name changed in this article for personal safety, flagged something suspicious. He saw a high concentration of seizures of DVDs in a small city in the Pacific Northwest. Then, he noticed similar patterns in other cities in a neighboring state.

“I suspected that there was a relationship between these seizures,” said Fletcher. “I noticed commonalties in the types of descriptions used on the shipping documents, the commercial quantities of the products, and the parties involved overseas.” That led Fletcher to conduct additional research to try to associate the different importers and shipping addresses. “I wanted to see if there could be a conspiracy or a counterfeiting ring,” he said.

The Motion Picture Association of America, MPAA, was beginning to conduct its own investigation. One of the association’s members, a major film studio, had received notices from CBP, alerting them that pirated knockoffs of their films had been seized at the border. The MPAA, a trade association that represents six of the major Hollywood studios, asked Fletcher for help.

Fletcher, in turn, reached out to the Department of Homeland Security’s investigative arm – Homeland Security Investigations or HSI. “I realized that there’s a certain segment of importers that are knowingly importing counterfeit goods to finance lucrative businesses,” he said. “To stop them, it requires criminal investigation, indictments, convictions, jail time and the seizure of assets to put the counterfeiters out of business.”

Within months, through the use of different databases, Fletcher and HSI special agents confirmed that a network of individuals was involved in a sophisticated film piracy operation. One of the importers had set up nearly 20 companies, using multiple names and identities. “We’re looking at a moving target. The criminals are always trying to be one step ahead of us,” said Fletcher. “They use methods and strategies such as setting up different businesses and business fronts, which make them suspect for money laundering.”

Fletcher worked with HSI to identify other rights holders who were potential victims. HSI reached out to several other federal law enforcement agencies for assistance. Their joint efforts culminated in the successful execution of federal search warrants in multiple locations. While the case is still pending, it underscores how a team approach is critical in fighting motion picture and television show piracy crimes.

Age-old problem

Piracy, the unauthorized reproduction or use of motion pictures, television programs or any other type of creative content, is not a new concept. The film industry has been plagued by piracy from its beginnings. However, Hollywood was hit especially hard when VCRs, videocassettes, and camcorders came on the market. The technology enabled people to duplicate content without payment, which led to financial losses for the industry, and illegal film distribution became rampant.

As technology has improved, the ability to steal products has become more and more sophisticated. “Today, we see criminal businesses that are established specifically to steal and upload pre-released or unauthorized content such as movies before they are released to DVD, while they’re still in the theaters, or sometimes even pre-released,” said Lev Kubiak, the director of the National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center, a multi-agency task force managed by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement/HSI in Arlington, Virginia.

“Traditionally, movies were illegally copied here in the United States. Someone would press discs or produce fake cover art for the films and then sell them on the street corner. But now, very little production is done in the United States. Most counterfeits are illegally produced in China,” said Kubiak. “During fiscal year 2013, CBP and HSI seized $1.7 billion worth of counterfeit goods; the vast majority was confiscated by CBP at the ports of entry. Ninety-two percent of that we believe came directly or indirectly from China,” he said.

A substantial number of those goods fell into the category of optical media, which include creative content such as movies, TV shows, video games or music in a format that is read through an optical ray on DVD, CD and Blu-ray disc equipment. During the last five years, optical media has been in the top-10 ranking of goods seized by the Department of Homeland Security for infringements on trademarks and copyrights. The largest number of seizures, 49 percent, were major motion pictures or boxed DVD sets of premium cable TV shows.

Real or Fake?

Higher quality knockoffs

“It used to be that a lot of the counterfeit goods weren’t as high quality as they are now,” said Michael Robinson, the executive vice president of global content protection for the MPAA. “The spelling on the packaging would be wrong or a Disney movie would have a Warner Bros. logo on it, so it was pretty easy to tell the genuine from the fake. But now, we’re facing the same problem that a lot of rights holders have. The counterfeits are exact copies of the originals with no misspellings, so it’s hard to tell just from looking at them.”

According to Robinson, the majority of movies are pirated in theaters. “It happens when somebody goes into a theater with a recording device and records it off the screen,” he said. To protect movies, Robinson says the association’s studio members watermark their films. “If a camcording theft occurs anywhere in the world, we’re able to identify the theater where the movie was shown,” he said. “The watermark is a fingerprint embedded in the film. We work with law enforcement authorities around the globe to identify and interdict that activity to put a stop to it.”

“Most illegal camcording occurs in Eastern Europe,” said Kubiak. “The illegal copy is then uploaded on the Internet and distributed globally through streaming or downloaded from illegal websites,” he said. “These websites don’t charge a fee. They make their money through advertising – the higher the popularity of the website, the higher the ad revenue,” explained Kubiak. “So the bad guys who are pirating these films make their money by stealing Paramount’s newest movie, giving it away for free on their website, and then profiting from the website’s advertising,” he said. “Websites like these become very, very popular and can make millions or hundred of millions of dollars a year.”

Another way that content is often stolen is during the legitimate manufacture of DVDs. “Some weeks prior to the legitimate release date of the DVD version of a film, when the public can go into a store in the U.S. and buy it off the shelf, the DVD has to be produced and shipped,” said Robinson. “There’s a whole supply chain process. Somewhere during that process, one of those DVDs could be stolen,” he said. “And it just takes one. After that DVD is stolen, it can be shipped or uploaded on the Internet and delivered to anyone.”

Deep economic loss

While many see piracy of movies and television shows as harmless, it’s not. The economic loss to the U.S. is staggering. According to a report issued by the U.S. Department of Commerce in March 2012, “Intellectual Property and the U.S. Economy: Industries in Focus,” intellectual property-intensive industries support at least 40 million jobs and contribute more than $5 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product. “When foreign countries steal that intellectual property or duplicate it illegally, they’re undermining the security of the U.S. and its economy,” said Kubiak.

The victims are numerous too. “What a lot of people fail to understand is that this is not a victimless crime. There are directly or indirectly 2 million people in the United States from various backgrounds who work for the film industry, and we support more than 100,000 businesses in all 50 states,” said Robinson. “It’s not just the big-name stars you see walking across the red carpet. It affects carpenters who are building sets, seamstresses who are sewing costumes, truck drivers, lighting experts, sound engineers, everything that you can imagine. It’s a huge industry and it takes a lot of people to produce films.”

Robinson also noted that the motion picture industry pays more than $16 billion in state and federal income taxes each year. “People look at it as entertainment. They don’t necessarily look at it the same way as they do other manufacturing jobs. But it’s just as important to the U.S. economy. We’re one of the industries that has a positive trade surplus around the world. We export more content than we import. So it’s a huge driver for the U.S. economy, and therefore, warrants protection.”

Piracy also has a chilling effect on independent film producers. Case in point is what happened to Ellen Seidler, a Harvard-educated filmmaker, journalist and journalism teacher, who, in 2006, decided to make a feature movie with her directing partner, Megan Siler, a UCLA film school grad. The two put up $250,000 of their own money to make their film, “And Then Came Lola,” thinking they would at least be able to break even. “I took out a second-mortgage, borrowed against my retirement, and went into credit card debt,” said Seidler, who is still paying off the debts she incurred during the film’s production.

At first, the film showed promise. In 2009, it debuted in front of a sold-out crowd at the Frameline Festival, a premier film event in San Francisco. Other festivals followed, but then within 24 hours of the film’s release on DVD, Seidler began seeing links to pirated copies on the Web. The download links were rapidly propagating and popping up everywhere. After a couple of months, the filmmakers had found more than 56,000 pirated copies and stopped counting. Seidler found the film on websites in a number of languages including Arabic, Russian, Turkish, Chinese, Spanish, Swedish and Czech.

Seidler tried to fight back. “Initially, when I found illegal copies, I tried to have them removed,” she said. But her efforts were futile. “You take one down and 10 more pop up.”

But what really infuriated the filmmaker was when she noticed corporate ads on the illegal sites that featured her film. “What I quickly discovered was that other people were making money off of the theft of my film, including a number of legitimate companies,” said Seidler. “It didn’t seem right to me, so I created my first blog to document the connection between piracy and profits, and to show how mainstream companies were profiting from this black market.” Seidler, who wants to educate others, has continued to write about piracy. “This is not just about something that happened to our film. This is the scenario that happens pretty much with every film.”

Motivating factors

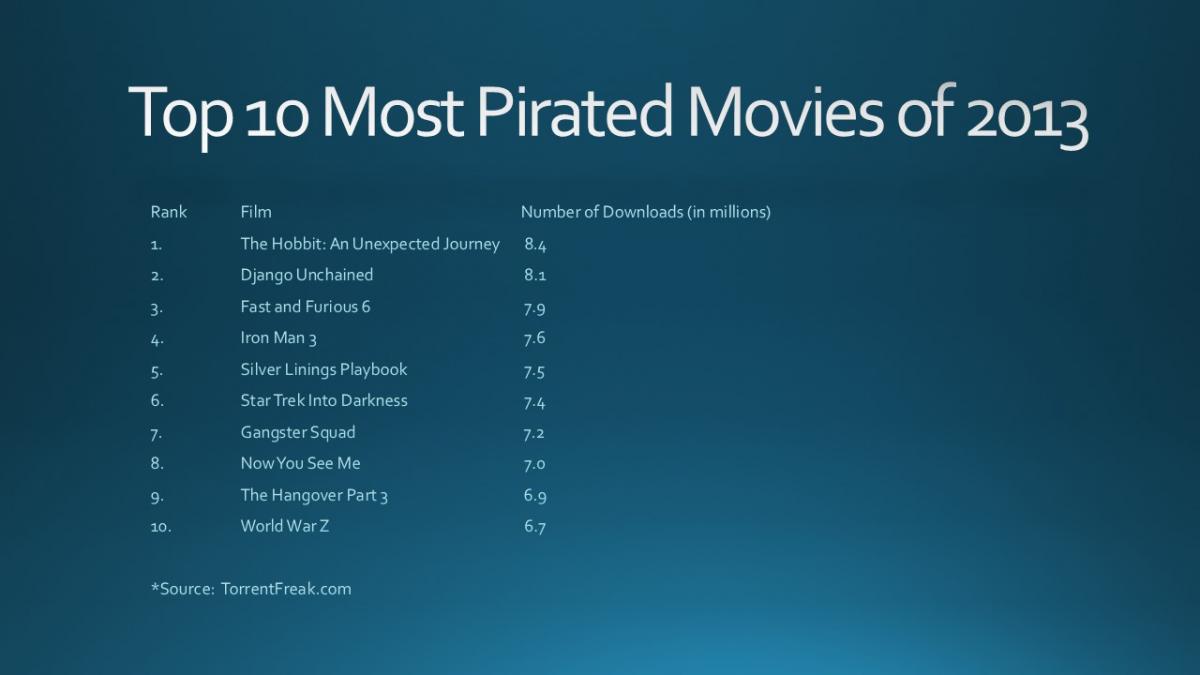

Film piracy is fueled by a number of factors. One of the key motivators is when movies and television shows are not released at the same time in different geographical territories. The time lag spurs viewers to watch pirated content because they don’t want to wait. One of the most publicized instances occurred last April, when the piracy rate of HBO’s fantasy series, “Game of Thrones,” reached such epic proportions in Australia that U.S. Ambassador Jeffrey Bleich made a plea to Australians to stop watching pirated episodes. In 2012 and 2013, “Game of Thrones” was ranked the No. 1 pirated television show by TorrentFreak, a file-sharing news site.

Pirating films is also a good source of money. “On average, it costs a hundred million dollars to make a film and bring it to market,” said Robinson. “If all you need to do is steal the film off the screen and remarket it, you don’t have all of the expense that goes into the production.”

It’s also a matter of perception. Many people don’t perceive piracy as a crime. “The public doesn’t seem to have a problem with piracy because they have this naive view that if something is on the Internet, it’s there for the taking,” said Seidler. “Companies like Google help perpetuate this because links to pirated sites are typically at the top of their search results. People think that if they find it on Google, it must be okay.”

But sometimes people aren’t aware that they’re buying pirated items. “Some of these sites look so legitimate that it’s hard for the average person to understand that he or she is at an illegitimate site versus a legitimate site,” said Robinson. “It’s much more difficult to know which sites are reputable on the Internet than walking down the street and deciding which shop to go in.”

Fighting piracy at the port

Combating piracy requires a coordinated effort. At the border, CBP evaluates goods to see if they pose a threat and if they violate any laws enforced by customs. If copyrights or trademarks are infringed, the goods are seized and prevented from getting into the stream of U.S. commerce.

The majority of pirated and counterfeit goods are shipped into the U.S. through international mail and express courier facilities such as Federal Express, DHL or UPS. One of the busiest, the DHL facility in Cincinnati, has the largest number of flights from Asia. During fiscal year 2013, a total of 16.4 million imported shipments came into the facility and 13.7 million exports went out.

“It’s pretty fast-paced. There are a lot of packages coming through here,” said Cory Bratton, one of the CBP officers assigned to the Asia team at the DHL facility. “Every package that comes here is subject to inspection and we select what we want to look at,” he said. “It’s just mind-blowing the amount of packages that go through here. There are boxes going in every direction.”

The CBP officers work closely with DHL. “We’ll go to the exam floor and DHL has already held each package we’ve selected to look at,” said Bratton. “Without their help, we wouldn’t get nearly as much done. But we also have to understand it’s a business for them and they’re trying to get as many packages through as possible,” he said. “We need to release the packages in a matter of minutes, sometimes less. They have to get everything out of here at a certain time so that it can be routed to the correct location to guarantee delivery for their customers.”

The number of intellectual property seizures at the DHL Cincinnati facility is high. “Our targeting percentage is about 60 percent, which means that out of every 10 shipments we look at, we hold six of them for violations,” said Eugene Matho, the assistant area port director of Cleveland, who oversees the Cincinnati DHL hub and two other express courier facilities in the region. “We don’t have enough officers in these locations for the volume that comes in and the turnaround time. If we had more staff, we could do a lot more.”

According to Matho, the trends for counterfeited and pirated goods are parallel to the trends for legitimate products. “When something is a very hot product, shortly thereafter we see the counterfeited or pirated version coming across the border,” he said. “For example, about five years ago, when cable television shows became popular, we saw the trend reflected in our seizures. Boxed sets of television and premium cable shows such as 'The Sopranos' and 'Sex and the City' were among the most pirated. Today, some of the hot items are 'Game of Thrones,' 'Breaking Bad,' 'The Walking Dead,' and Disney movies are always popular and infringed.”

Investigating criminal activity

When CBP finds illegal shipments that appear to be involved in criminal activity, HSI is contacted for further investigation. To expand its reach on intellectual property rights cases, HSI started working more closely with state and local law enforcement. “We realized that we were never going to arrest or seize our way out of this problem, so it was critically important that we got state and local law enforcement involved,” said Kubiak.

One significant example occurred, in 2011, after CBP officers at the Cincinnati DHL facility noticed that hundreds of shipments were being sent to someone by the name of Joseph Palmisano in Bartlett, Illinois, a northwest suburb of Chicago. “I was targeting shipments from Asia and saw that Palmisano had received about 800 shipments over the last five years. He was a heavy importer,” said CBP Officer S. Burns.

Burns stopped a number of the shipments. All had shipping labels that described the contents as “teaching supplies” or “bread boards.” But when he examined the packages, he found DVDs of movies and TV shows inside.

Burns knew that something was wrong. “There were misspellings in the film descriptions on the back covers,” he said. “The lettering was crooked and the routing of the packages was from Hong Kong.”

Burns sent a sample to a CBP import specialist in Cleveland. “The packaging looked like it could be counterfeit, but a CBP officer can’t make that determination. The only one who can determine that is an import specialist,” he said.

After Burns suspicions were confirmed, he seized the shipments. He also contacted HSI’s Chicago office. The special agent assigned to the case, Uday Devineni, immediately saw there was a problem. “There were 25 seizures over a six-week period from mid-August 2011 until the end of September 2011. And that’s just what we caught,” said Devineni.

The HSI special agent decided to contact the Bartlett Police Department. “We were looking to foster relationships with local agencies and we felt this was the most effective route for us to go,” said Devineni, who explained that oftentimes more violent crimes take precedence over counterfeit investigations. “It’s a matter of allocating resources. In the city of Chicago, there are so many other crimes such as gang violence and murder.”

Local assistance

The Bartlett Police Department was receptive to taking the lead on the case, and quickly noted that there was something odd about the recipient’s mailing address. “The packages were all addressed to Joseph Palmisano, Joseph, Joe Joe, or Joe,” said Detective Tom Alagna from the Bartlett Police Department. “He was using three different addresses—his actual address and two fake addresses that would have been located next door to his house if they existed.”

But within a month, the shipments stopped. “We hit a dry spell. Nothing was coming in,” said Alagna. “I was in constant contact with CBP, HSI, and we did several hours of surveillance on the house. Cars never moved. Nothing happened.”

Then as luck would have it, the detective drove by the house on patrol one day and saw that Palmisano’s garage was loaded with boxes. “We knew we couldn’t get a search warrant just based on seeing boxes in a garage,” said Alagna. However, shortly thereafter, on June 29, 2012, Alagna received a call around midnight from CBP Officer Burns. “He told me he was doing a routine check of imports and noticed there was a package scheduled to arrive at Palmisano’s address from Hong Kong,” said Alagna. “He said that the package was seized. When he opened it, it contained 130 counterfeit DVDs.”

The next day Burns contacted Alagna again. Another shipment from Hong Kong addressed to Palmisano was arriving in Los Angeles. “He had the package rerouted to Cincinnati so that he could seize it,” said Alagna. Then Burns sent the shipments to Alagna so that the detective could obtain a search warrant for Palmisano’s home and on July 5, 2012, law enforcement, with help from the MPAA, made a controlled delivery of the counterfeit goods.

More than 100,000 DVDs of counterfeit movies and television shows were found in Palmisano’s home, making it one of the largest counterfeit DVD seizures in the Midwest. “We had two 24-foot moving trucks completely filled with DVDs,” said Alagna. The estimated manufacturer’s suggested retail price for the DVDs was $1.35 million.

“When we spoke with Palmisano, he told us that last year he had sold more than $660,000 of counterfeit films in a 10-month period. It’s jaw dropping,” said Alagna, noting that most of the merchandise was sold on Amazon.com.

The case was prosecuted at the state level and Palmisano, who was charged with one count of unlawful use of recorded sounds and images, pled guilty. He was sentenced to 30 months probation, 120 hours of community service, and was required to pay $5,200 in fines to the MPAA, and $9,800 in restitution to the Bartlett Police Department.

Despite the fact that Palmisano did not go to jail, the case was successful. “It was a team effort,” said Alagna. “Everybody’s contributions were substantial and very, very critical. Without one of those pieces, the investigation would not have had a successful end.”

Partnering internationally

CBP, HSI, and other law enforcement agencies also fight film piracy on an international level. “We share data with a vast number of countries to help them increase their seizures through our customs mutual assistance agreements,” said Kubiak. “We also provide training overseas to state, local, federal and regional investigators and customs officers globally. Both CBP and HSI work with the Department of State, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and the Department of Commerce.”

In December, CBP and HSI partnered with 10 law enforcement agencies from Europe and Asia in a Cyber Monday sting operation that resulted in shutting down 706 websites that were selling counterfeit goods, including pirated movies and television shows. The worldwide operation, the largest to date, was part of an online digital theft initiative called Operation in Our Sites, which was launched by the Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center in June 2010.

Training at the ports

Rights holders also play a key role in fighting film piracy. The MPAA provides training at the ports. “We partner with other brand holders and conduct training sessions for CBP officers and import specialists,” said Marc Lorenti, the MPAA’s director of investigations for North America.

The training, which is organized by the International AntiCounterfeiting Coalition, is not specific to motion pictures. It includes different companies such as Louis Vuitton, Burberry, Chanel, Rolex and others. “It’s a very aggressive program,” said Lorenti.

“From a visual perspective, we teach the CBP officers and import specialists how to determine a genuine DVD from a fake, not only by looking at the packaging, but also by looking at the disc itself.” One key component that quickly identifies if a film is genuine is the IFPI code, issued by the International Federation of Phonographic Industry as a means of authentication. “It’s like a fingerprint etched on the core of the disc,” he said.

According to Lorenti, the training, which began last September, is already paying off. “The leads are coming in on a regular basis from CBP officers in the field who identify shipments that are coming in. As recent as two weeks ago, CBP officers at Bradley International Airport in Connecticut reached out to us directly to authenticate shipments that had come into that port. We responded the next day,” said Lorenti. “We were able to authenticate the shipment on site as being counterfeit, and then worked in conjunction with CBP to refer the case over to HSI.”

The MPAA is also developing a software tool that will help CBP officers identify counterfeit DVDs more quickly. “We’re testing this tool right now,” said Robinson, who hopes to share the technology more broadly with CBP. “We want to be part of the solution and we recognize that we have a responsibility to do that,” he said. “We’re not just going to CBP and other agencies and saying, ‘Help us. We’re a victim. It’s your problem to correct.’ We’re in this together.”

Closing the gap

Others such as HBO, a premium television networks with reported earnings of $1.8 billion in 2013, and 127 million subscribers in nearly 70 countries worldwide, have found ways to close the gap on the delivery of their programming as technology has evolved. “Our production team at our studio has worked extremely hard to streamline the process for getting the content to all of the international affiliates and distribution partners in a way that allows them to air the show much closer or exactly the same day, date and time as it is shown in the U.S.,” said Stephanie Abrutyn, vice president and senior counsel of litigation and anti-piracy for HBO. “Over the last 10-20 years, we have literally shifted from a model where someone had to take a hard copy of a program and put it on an airplane to every single one of these countries to a system where we can push a button and deliver it digitally in seconds.”

Still other challenges remain. “One of the biggest challenges we have is the volume of counterfeit and pirated goods that are coming into the country,” said Therese Randazzo, CBP’s director of intellectual property rights policy and programs in Washington, D.C. “The laws under which we’re operating were put in place long before the Internet enabled easy sale of counterfeit and pirated goods directly to consumers. These shipments come in small packages at mail and express courier facilities as opposed to cargo, so it takes a lot more resources to examine and make infringement determinations,” she said. “We need a simpler, more streamlined process where we don’t jump through quite so many hoops. The Internet has changed importation of counterfeit and pirated goods, but the laws haven’t kept up,” she said.

But the real key is enlisting the public’s help. There are a number of resources to access movies and TV shows legally. The MPAA’s website www.WheretoWatch.org is one of them. “Film piracy is not going to be eradicated until we eliminate consumer demand,” said Randazzo. “If we’re ever going to be successful in solving this problem, we need to educate the public and get them onboard.”

*Answer to opening question: All of them are fake.

A Higher Level of Protection for Rights Holders

T o protect rights holders, CBP has set up a recordation process to register trademarks and copyrights with the agency. “Sometimes trademark and copyright holders are unaware of the extent of the protection that CBP can afford them, so they don’t ask us for help,” said Therese Randazzo, the director of the intellectual property rights policy and programs division of CBP’s Office of International Trade in Washington, D.C.

By recording trademarks and copyrights, rights holders receive a higher level of protection. “We provide information to the rights holder about the parties involved in the seizure, the quantity of goods, the port the shipment entered, when the entry occurred, who shipped the merchandise, and who imported it,” said Randazzo. “That gives them information that they can use if they want to take legal action. Recordation also gives them access to samples of the infringing merchandise. But they would not receive any of this if they’re not recorded.”

Such was the case a few years ago when CBP officers discovered shipments of perfume that infringed HBO’s trademark ‘Sex and the City.’ “We told them that we were seeing a lot of perfumes that were using similar names. We knew there was a show and a movie, but we didn’t know if this was a product that they were making. We wanted to know if it was authentic,” said LaVonne Rees, a CBP international trade specialist in Los Angeles.

“We had seen suspected counterfeit fragrances before and couldn’t act on it because HBO wasn’t recorded with us. The company wasn’t registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office,” said Rees. But that all changed. “In April 2011, HBO came to us and said, ‘We finally have this recorded. Here is our trademark number and now we want to do something about it because we can.’”

During fiscal year 2011, CBP seized imports of counterfeit perfume valued at nearly $51 million. The fake fragrance that was most frequently intercepted infringed the Sex and the City trademark. The 48 shipments that were seized had a domestic value of $5.6 million. If the trademark had been genuine, the manufacturer’s suggested retail price of the perfume would have been worth more than $34 million.