Cleared for Landing

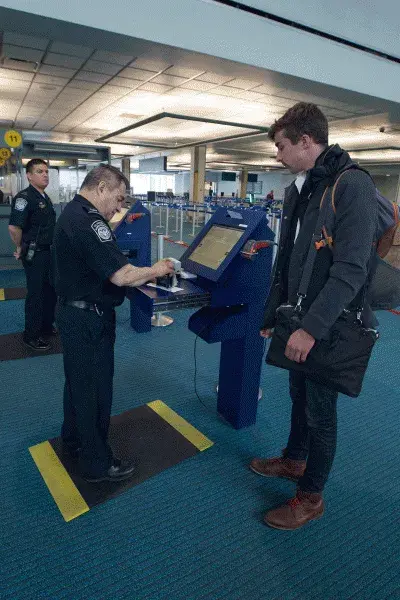

The airport international passenger queue for U.S. Customs and Border Protection processing moved steadily. It was peak time for flights and the inspection area hummed with travelers wheeling their luggage and speaking with CBP officers. At a self-service passport kiosk, where many passengers can scan their travel documents and get their photo snapped, one older woman laughed at her image in the kiosk camera.

After completing the kiosk process in about two minutes, the woman walked over to speak with a CBP officer, who asked the reason for her visit and a few other questions. Cleared to go, she rolled her carry-on through the exit door under a large “Welcome to the United States” sign and entered a concourse lined with shops and restaurants — in Vancouver, Canada.

This passenger had just experienced — like millions of others this year — CBP preclearance operations. When these travelers arrive in the U.S., they simply gather their luggage and leave the airport, no further CBP inspection needed.

CBP personnel at 15 preclearance airports worldwide inspect travelers for compliance with U.S. immigration, customs and agriculture laws before the travelers board a U.S.-bound aircraft. Passengers and their luggage also must pass security screening equal to U.S.Transportation Security Administration inspection before boarding.

Preclearance operations — begun in Toronto in 1952 and now in Aruba, the Bahamas, Bermuda, Canada, Ireland and the United Arab Emirates — has gained prominence since Sept. 11, 2001.

“We need to secure international travel, and we also want to facilitate its growth and to provide a welcoming experience for travelers coming to the U.S.,” said CBP Deputy Commissioner Kevin K. McAleenan. “International travel to the U.S. continues to grow at 4 percent to 5 percent each year since 2009. We need to encourage this growth while addressing threats to commercial aviation as early as possible in the travel cycle."

Preclearance demonstrates the protection value of pushing homeland security out beyond U.S. physical borders. It creates an early line of defense, stopping possible law breakers before they board. And for the traveling public, it reduces crowding and wait times upon their arrival at some of the busiest U.S. airports.

“It was great. I’ve been through many times and it’s always a lot quicker [than inspection in the U.S],” said a sweatshirt-clad young man after going through CBP preclearance at Vancouver International Airport. “You know it’s done and you don’t have to worry about it on the other side. … This is way easier. And I’ve done the same thing in Toronto with preclearance and yeah, way better.”

Moving quickly, securely

With newer preclearance baggage systems like the Vancouver airport process, travelers drop off their labeled and checked luggage, which is then bar-code scanned,

photographed, X-rayed and weighed by airport personnel. The bags then leave the passengers’ custody and enter a separate, secure processing system.

This system benefits travelers arriving at preclearance from other flights. “The connecting customer has the ability to move directly through the CBP process without having to stop to pick up their bag,” said Steve Hankinson, vice president of operations and information technology for the Vancouver Airport Authority. “The airline will take their bag and drop it off and it will go through the system. So the bag will go from tail to tail, from airplane to airplane, and the customer then moves through the CBP process.”

When passengers using the new baggage system meet with a CBP preclearance officer for inspection, the officer pulls up all the baggage information on a screen. After questioning the traveler, the officer can designate that one or all of the bags be retrieved for closer physical examination. The passenger at any time can also be directed to a secondary CBP inspection location, just as at a U.S. port of entry.

The baggage data in this modern system gives officers the background intelligence they need to ask the traveler the right questions. “For example, if they tell the officer that they’re going to the U.S. for a week, the officer can ask, ‘Why are you not traveling with enough clothes to stay for a week?’” explained Lee DeLoatch, area port director for CBP Vancouver Preclearance. “Or the officer can come back and ask, ‘Why are you bringing so much luggage? How long do you plan on staying?’ The passenger says that he’s traveling for pleasure, but his intent may be to live in the United States.”

Preclearance enables CBP to sustain tight traveler and baggage security while speeding the process overall for the traveling public and for the agency’s private sector partners.

“The customer really wants to move through an airport process as quickly as possible and as easily as possible,” said the Vancouver Airport Authority’s Steve Hankinson. “And as part of that preclearance process, they can get all of the check-in, drop the bags, move through security, and move through CBP quickly. All of that accelerates the whole speed at which a customer moves through the process.”

What’s in it for passengers, airports and airlines?

|

|

More than a quarter million international air travelers on average arrive daily at U.S. airports, according to CBP, and the number is expected to grow. More travelers could mean more waiting to clear CBP, but CBP innovations like preclearance cut the queues.

Precleared passengers landing in the U.S. already have passed CBP processing, so they land, grab their bags and depart at U.S. international airports just like domestic travelers. This means fewer people stand in CBP queues upon arrival, shortening the lines for everyone.

Also, without the need for CBP processing, precleared flights can arrive at domestic gates in the U.S., which equals less running between gates, faster connections and ultimately fewer missed flights.

Preclearance avoids peak congestion periods by staggering inspections as passengers trickle in prior to their departure. Travelers check in in small groups, often from connecting flights. CBP preclearance facilities remain open to continuously process them as they arrive, with no inspection closures between flight arrivals, as at U.S.-based CBP facilities.

Easing and expediting passengers through airports via preclearance allows airports and air carriers to increase business in sometimes surprising ways.

|

|

With preclearance, airports and airlines can expand the number of flights and routes and reduce international airport congestion. For example, some precleared international flights now land at New York’s LaGuardia Airport, shrinking bottlenecks at JFK International Airport and creating new direct airline routes.

“Air carriers can fly on a hub-to-hub basis,” said Dylan DeFrancisci, CBP director of preclearance operations. This speeds time for flight connection and saves airlines money on gate fees, which are significantly higher at international terminals.

In fact, when a plane must land at an international terminal and its next flight is domestic, the airline often must pay for the aircraft to be towed to the domestic terminal.

“One air carrier departing from Dublin Airport used to fly into terminal four at JFK Airport every day and tow the aircraft to terminal five every day,” said DeFrancisci. “It was about $800,000 per year in towing costs and took about two hours. They eventually requested preclearance, and once it was enacted they not only saved money, but also got the passengers to their destination faster and the plane up in the air quicker by landing at a domestic terminal.”

When CBP at a U.S. airport denies a traveler entry into the country, the airline foots the bill to fly the passenger back to the country of origin. When CBP preclearance prevents a passenger from boarding, the airline immediately has saved the cost it otherwise would incur had the passenger flown to the U.S.

Golden airport business opportunities

The popularity of preclearance boosts the number of passengers, flights and routes to the U.S., giving preclearance airports a competitive edge. U.S. preclearance departures rose 34 percent in 2014 over the previous year at Dublin Airport, a preclearance site, according to a Dublin Airport Authority report. This ranked the airport as the seventh busiest European hub for trans-Atlantic flights in 2014, the airport reported.

Preclearance also translates to bigger business on the ground for airports. “The growth in connecting traffic has resulted in additional demand for food and beverage and for retail services,” said Steve Hankinson of the Vancouver Airport Authority. The growth in air traffic has “increased the benefit to the airport because we’re able to do more business post-CBP with the customer,” Hankinson said, “and that results in revenue being generated for the airport.”

Vancouver International Airport invested big in retail and restaurant infrastructure enhancements in the areas downstream of CBP preclearance processing, and it’s paying off. The airport’s 2014 duty-free sales in its U.S. departure terminal generated more than 10 million Canadian dollars.

CBP worked with the airport and Canadian Air Transport Security Authority, or CATSA, to realign the passenger screening process to place the CATSA preboarding screening before CBP’s screening. “The agencies signed an agreement that CATSA would meet U.S. TSA security standards,” said CBP Vancouver Preclearance Area Port Director Lee DeLoatch. “Then the airport could put duty-free shopping after the CBP inspection. The vendors agree that they will collect the duties and at the end of each month, they cut a check to the U.S. government for those.”

“Once passengers have passed CBP, they’re able to shop freely and purchase items knowing that they don’t have to go back and declare,” added DeLoatch. “So it actually makes the passenger’s experience that much greater.”

After retail and restaurant sales were located after preclearance processing, sales of duty-free items at Vancouver International Airport shot up 30 percent, said DeLoatch.

Expanding preclearance

The advantages of preclearance for national security and travel facilitation are so great that in 2014 CBP and the Department of Homeland Security announced a formal process for international airports to apply to host preclearance operations.

“The best means we have to disrupt and deter terrorist threats is the strategic stationing of CBP law enforcement personnel overseas, preclearing travelers before they board U.S.-bound flights,” said DeFrancisci. “CBP intends that, a decade from now, one in three air travelers to the U.S. will be precleared, up from 16 percent in fiscal year 2014.”

DHS cooperated with the Departments of State and Transportation on the airport preclearance application parameters. At the close of the application period, more than two dozen foreign airports had expressed interest. “DHS sent technical teams from DHS and State to visit each candidate airport to assess the feasibility of preclearance operations at each location,” said Randy Howe, director of the CBP preclearance expansion integrated program team.

DHS and State evaluated and prioritized all interested foreign airports. Each applicant was rated on four criteria: facilitation, security, feasibility and strategic impact with multiple subcategories, including items like national security, passenger facilitation, wait-time impact and economic benefits. “This created a composite score that drove the final decision,” said Howe.

The 10 airports identified in May 2015 as candidates for preclearance were: Brussels Airport, Belgium; Punta Cana Airport, Dominican Republic; Narita International Airport, Japan; Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, Netherlands; Oslo Airport, Norway; Madrid-Barajas Airport, Spain; Stockholm Arlanda Airport, Sweden; Istanbul Ataturk Airport, Turkey; London Heathrow Airport and Manchester Airport, United Kingdom. These sites represent some of the busiest departure points to the U.S. — nearly 20 million passengers traveled from these 10 airports to the U.S. in 2014.

CBP has been negotiating the terms of preclearance with each of the candidate airports. The parties also will work out the scale and scope of preclearance operations, such as the numbers of flights CBP processes, the terminals, the hours and potential increases over time.

As the airports will pay for roughly 85 percent of preclearance costs, “they have the ability to negotiate and design the model they want,” said DeFrancisci. They can start with fewer flights precleared and scale up based on their experience, “seeing how their baggage systems work and how they queue and stage their passengers,” he added.

CBP will work with each airport to develop a model that best fits the airport and the air carriers at each site. Each location’s geography and climate will create a learning curve for airport, airline and CBP partners, adjusting flights and staffing as the seasons change. For example, Abu Dhabi airport, a current preclearance site, gets “some pretty severe fog,” said DeFrancisci. “Out of nowhere, this fog will come in and cripple the airport.” He said that the week that preclearance opened, Abu Dhabi had 10 flights delayed by fog.

CBP, the airlines and Abu Dhabi airport adjusted their schedules to deal with the fog and the Persian Gulf heat. CBP began a midnight shift, which avoids the sun rising, heating the ground moisture and creating fog. Everyone has a stake in the success of preclearance and they’re willing to work together, said DeFrancisci.

Pre-inspection: Unique to British Columbia

One CBP security process reflects the special, historic relationship between the U.S. and Canada: pre-inspection.

“Pre-inspection only deals with the admissibility portion of the CBP inspection – in other words, whether or not people have the right to travel to the United States,” said Donovan Delude, port director for CBP pre-inspection at Victoria, British Columbia. “Whereas preclearance speaks to the customs, agriculture and the admissibility-immigration portions.”

CBP pre-inspects travelers to the U.S. at five sites with three different border-crossing modes of transit: ferry, cruise ship and train. CBP officers in Vancouver, who also staff the airport preclearance operations, travel as needed to the city’s train station and cruise port to process pre-inspection travelers. CBP maintains a staff of 13 in Victoria to manage pre-inspection for three ferry lines.

Pre-inspection agreements between the U.S. and Canada predate 9/11 and the formation of CBP. Estimates place the start of immigration pre-inspection in the early 1900s at Victoria, a tourist destination.

In the summer, each U.S.-British Columbia ferry line adds crossings to their schedules “and it’s busy!” said Delude. “The Washington state ferries are about 20 miles away from here. And we have the two different terminals here in Victoria, so we have to spread our people out. It’s a logistical dance at times to make all of it work.”

Cruise ships bound for Alaska from Vancouver have benefitted from pre-inspection services for more than 30 years, said Carmen Ortega, manager of cruise services for Port Metro Vancouver. “Nobody wants to spend half their day at their first port of call being processed,” said Ortega. “Pre-inspection allows passengers to disembark in Alaska in a more seamless manner.”

The growth in popularity of Alaska cruising raises the stakes for cruise lines, Alaska tourism and efficient CBP processing. “The number of Alaska ports of call hasn’t changed,” said Ortega. “What we have seen is an increase in the size of ships. A ship like this one [the Ruby Princess] carries 3,200 passengers. When we started this business 40 years ago, the biggest ship had maybe 600 passengers.”

Ortega credits the collaboration among CBP, Port Metro Vancouver and the Canada Border Services Agency for the smooth, efficient passenger processing.

After a hiatus of 14 years, pre-inspection began again in 1995 for the Amtrak Cascades trains, which travel a scenic route from Vancouver to Seattle by Pacific Northwest mountains and waterways. The efficiencies of pre-inspection for this cross-border train route are clear, according to Gay Banks Olson, assistant superintendent of operations for the Amtrak Northwest Subdivision.

“Amtrak and the states of Washington and Oregon [which fund the Cascades operation] are committed to reducing travel time and increasing service,” said Olson. “As travel time decreases, your ridership goes up. So even 10 to 15 minutes for us makes a big difference in people’s decisions on what transportation mode to utilize.”

Close cooperation between CBP and the transit stakeholders sustains the success of pre-inspection. The Victoria ferries are “constantly giving us updates on the boats as far as loads they have coming in, what their expected passenger list is going to look like,” said Delude from CBP. “The Victoria Clipper is a smaller boat. If the weather may cause issues, they will ask CBP to change inspection time so the boat can depart and beat the weather and CBP does its best to help the boat stay ahead of a storm.”

“So we’re in communication with our stakeholders on almost a daily basis,” Delude added.