Marine Life

Churned by a stiff evening breeze, the sea grew rough as the crew aboard a sleek interceptor searched in the dark for a reported smuggler. Then a blip with coordinates to the suspect flashed on the boat’s radar. Wasting no time, the commander of Air and Marine Operations’ 39-foot Midnight Express hollered for the crew to hold on and pushed the throttles full forward.

The boat’s four 225 horse-power Mercury engines roared. As the accelerating hull hit the swells, it boomed like a kettle drum and sprayed water over the deck with a hiss. Bouncing from the waves at more than 50 knots, the vessel at times became airborne for an instant then slammed onto the water with a hollow thud, shaking the boat.

As the interceptor sped to its target, the crew checked their equipment and prepared for the unknown. That blip could be anything from a family setting sail to a ship overloaded with illegal aliens to a similar high-speed vessel with well-armed runners determined to deliver their contraband.

Using night-vision goggles, the navigator finally spotted the shrouded vessel and shouted headings over the din, guiding the commander through the dark for the intercept.

The gap rapidly narrowed. Now, just feet away, the commander gave the signal. Instantly, the interceptor’s powerful flood lights and blue strobes illuminated the craft and the surrounding sea, stunning the unsuspecting subjects. The pursuers stood ready to board.

"Failure to heave-to [stop] is a felony," said Martin "Marty" Wade, the National Marine Training Center’s director since 2012.

Wade’s law enforcement career goes back to 1995, starting as a U.S. customs inspector and later a marine enforcement officer in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. "There were only a handful of us back then," he recalled. Wade advanced to a marine supervisor and marine director in Miami and eventually served as director of marine operations in Washington, D.C., before arriving at the center.

While the simulated chase and all its drama happened as described, marine interdiction agents crewed the suspect craft. The episode is one of many realistic experiences those attending AMO’s National Marine Training Center in St. Augustine, Florida, can expect and where U.S. Customs and Border Protection along with other federal, state, local and even foreign law enforcement organizations turn to keep their maritime skills sharp. International participants have included law enforcers from Paraguay, Malaysia, Ecuador, French West Indies and Colombia.

Unit was among those benefiting from the National Marine Training Center’s

small classes.

Immense task

More than 500 marine interdiction and U.S. Border Patrol agents visit the center every year, taking courses covering basic and advanced maritime skills, recurrent certifications and specialized tactics used to protect the nation’s coasts, lakes and rivers.

That job is accomplished in a remarkably nondescript building with two classrooms and adjoining dock that accommodates 30 vessels.

"Don’t be fooled by our small size," Wade stressed.

Just six AMO and six U.S. Border Patrol instructors teach 50 classes per year. In 2016, they chalked up an amazing 25,700 student training hours. Naturally, the high demand means a heavy workload, but it also means small classes so agents receive more one-on-one training.

Instruction is so valuable and comprehensive that members of the U.S. Navy special warfare units, special warfare combat craft operators and the Navy’s sea, air and land or SEAL special operations force train at the center.

Vessel commander, marine instructor, tactical boarding officer, marine tactics instructor, small boat interdiction and use-of-force are among the classes in most demand where participants confront multiple law enforcement challenges and practice maneuvers not possible in the field.

At the same time, the center strives to keep courses up-to-date to tackle evolving threats. "If we’re not moving ahead, we’re moving backwards," Wade said. "I want our marine agents to come through the door and be excited to train. The last thing I want to hear is ‘your training is not relevant.’"

Academics and application is balanced and everyone is trained to the same high standard regardless if they patrol the Rio Grande, the Great Lakes or the South Florida coast.

Improving marine units through standard training is central to the center’s mission, which delivers a highly skilled and mobile force that can quickly deploy to any of CBP’s marine locations.

Standardization allows regions to do more with limited resources, said Jeff Eccles, a supervisory marine interdiction agent from the Great Lakes Air and Marine Branch taking the vessel commander recertification course. Eccles said his region regularly augments locations in other parts of the country. "You need to rely on those you don’t normally work with during the year," he added.

Supervisory Marine Interdiction Agent and Instructor Ken Kilroy points out the tactics to expect when the class takes to the water.

Hitting moving targets at the right spot can be tricky as Supervisory Marine Interdiction Agent Chris Gallaspy from the Corpus Christi Marine Unit, Texas, takes careful aim.

Practicing tactics to safely board a vessel is an important part of the National Marine Training Center’s curriculum.

Agents typically spend a half day in class studying the procedures they’ll later practice on the water. Settings replicate real-world possibilities, just as the Midnight Express crew confronted during their evening intercept.

Procedures for successful intercepts, for instance, require teamwork and challenge vessel commanders to mentally picture the boat’s path, calculate position by course and speed, monitor the radar and listen for headings all at once, said Andres "Andy" Blanco, a supervisory marine interdiction agent and instructor. "Most suspect vessels won’t know you’re there," he pointed out.

"This job is for people who can think quickly and react," offered Antonio "Tony G" Gammillaro, a supervisory marine interdiction agent from the Miami Marine Unit, taking the vessel commander recertification course. "When you’re only feet from someone at night, no lights, it’s one of the most challenging jobs in all CBP."

As real as can be

Tactics to apprehend craft whether for a document check, inspection or for any reason is an important part of the program.

Agents in training chase a craft crewed by instructors playing the suspects who apply all the tricks evaders use to escape. The instructors deliver.

They zigzag. They dodge. They make sharp, abrupt turns, sometimes banking so forcefully the top side of their vessel nearly skims the water. But like a chess game, the pursuers anticipate and thwart each break-away.

Another boat intercepts. The commander maneuvers from one side of the fleeing craft to the other, studying its occupants. That assessment determines the tactics agents will use when boarding a vessel. Throughout the exercise, agents communicate and coordinate and there’s a primary boarding officer in charge, Blanco said.

Then it begins again. Another crew becomes the bad guys and another vessel commander takes the interceptor’s helm.

To ensure safety, two interceptors will parallel each side of a captured but overloaded vessel. Just as a bicycle rider will fall without enough forward speed, an overloaded boat can capsize for the same reason.

Runners can ultimately be stopped using shotguns that shoot projectiles designed to disable engines. Before resorting to disabling fire as it’s called, agents will first use other methods such as projecting authority and verbal commands. If those tactics are unsuccessful, they will fire warning shots toward the vessel.

Since disabling fire training isn’t authorized in the field, the center offers plenty of opportunity. Live fire is done several miles at sea, in "blue water." Blue water defines the open ocean, where the shore is just a line on the horizon.

"You never know who’s out there—murderers trying to escape, weapons traffickers, those with warrants," said Scott Leach, supervisory marine interdiction agent and the center’s deputy director. "That’s why we invest so heavily in our vessel commanders."

Wade recalled a boat trafficking Haitians from the Bahamas to Florida. That night, winds were brisk and waves topped seven feet as their vessel raced for the beach, now just 50 yards away. When the smugglers realized the breaking surf prevented them from reaching the shore, they ordered the Haitians to swim the rest of the way. Many couldn’t. The next morning, bodies were found along West Palm Beach. "Smugglers have no regard for life," Wade said.

Disabling fire

Shooters practice disabling fire on plastic outboard engines and human torso dummies affixed to a bullet-riddled target craft at the end of a long line being towed by another vessel. They role play the pursuit vessel and the conditions are challenging. Their vessel bobs from side-to-side, spray fills the air and there’s a brisk wind. Agents hand out shotguns, ammunition and ear protection, yelling over the engines noise. Today, disabling fire won’t be easy.

The target approaches. At the vessel commander’s signal, the shooter goes into action and directs a rapid, ear-ringing fusillade at the dummies. Then the exercise repeats—another commander and shooter will show their skills.

Center staff instruct on six interceptor vessels. Four are long and sleek multi-engine boats with pointed and extended hulls ranging from 39 to 41 feet that can reach speeds of nearly 70 miles per hour. The newest interceptor—and the center’s largest—is 41 feet with four 350 horse-power engines. It weighs 22,000 pounds—nearly 6,000 pounds more than the other three—and can travel 74 miles per hour.

AMO’s other two interceptors are SAFE boats: 33- foot and 38-foot vessels. The smaller craft at 13,300 pounds has three 300 horse-power engines and can travel 51 miles per hour. The other weighs 18,000 pounds has four 300 horse-power engines and tops out at 57 miles per hour. SAFE stands for Secure All-around Flotation Equipped, denoting the vessel’s wrap-around foam collar, providing added stability and buoyancy.

Training also covers the riverine world—rivers and lakes, where the Border Patrol operates 207 vessels.

In the bay just off the center’s dock, U.S. Border Patrol agents prepare to tow a disabled boat. It’s a delicate task. As their 21-foot riverine shallow draft vessel, or RSDV, gently glides alongside the stranded boat, the agents tell the occupants how to prepare for the tow. When the two vessels finally touch, agents unravel coiled lines and carefully tie the two craft together. In this case, the RSDV performs a side tow.

Supervisory Border Patrol Agent and Instructor Mike Arietta evaluates the maneuver. "Make sure they understand what you want," he tells them. "It’s one of the most dangerous times when two boats are next to each other. You can lose fingers."

Agents practice two types of towing, Arietta said— side tows for short distances in calm water and stern towing for long distances in rough water.

RSDVs are perfect for shallow water, said Border Patrol Agent Alberto Casasus from the Del Rio Sector, taking the initial vessel commander course. Casasus patrols Lake Amistad, a lake that extends into Mexico.

By funneling water through its 260 horse-power water-jet engine, an RSDV can hydroplane, he said. "You can stop in 11 inches of water," Casasus noted, or operate in "just four inches if you keep moving." RSDVs can travel nearly 35 miles per hour.

SAFE and RSDV craft, 12-foot inflatable powered boats, air boats and 16-foot, low-draft connectors that resemble small recreational craft, are used at the center for riverine and special operations training. Agents can earn certifications in any of these vessels, said L. Keith Weeks, a supervisory border patrol agent and instructor.

environment—rivers and lakes. Training includes operating low-draft and

inflatable craft used for patrolling shallow water or special operations.

Calling the shots

While speed, tactics and firepower give AMO agents the edge, the real advantage is the training and experience that allow AMO vessel commanders to authorize disabling fire without supervisory concurrence. This authority gives AMO the capability to disable non-compliant vessels, stop dangerous pursuits quickly and prevent these vessels from reaching our shores. CBP is the only federal agency that delegates this authority to its operators regardless of rank, Wade confirmed. "There’s a tremendous amount of trust and responsibility given to our agents when making critical use-of-force decisions," he said. "That’s huge." Since 2003, AMO has engaged in 126 events involving marine warning and disabling fire.

However, the center prepares commanders to use good judgment since they’re accountable to act within policy. For example, deciding when and where to pursue a vessel. Offshore pursuits give agents more control and little chance for violators to escape.

Thanks to a business mindset, the center gets the most from its $1.08 million dollar budget, where efficiency and quality training go hand-in-hand.

The center has its own fueling station. Buying in bulk cuts costs and time since vessels no longer travel to offsite marinas to fill up at retail prices. To eliminate airfare, attendees from Florida and Louisiana must drive to the center. Rental cars are shared and the center negotiated with three area hotels to provide rooms at $33 below the government rate. Those measures alone save more than $60,000 per year, Wade said, while the center pumps more than $600,000 into the local economy.

More savings are captured through the center’s maintenance facility which keeps vessels in top shape at well below the going rate. Training vessels demand more attention because the constant maneuvering places greater stress and wear on the craft compared to regular operations.

"We never had to keep a class over because of maintenance issues," Wade said. "Our dedicated technicians work day and night to support the mission."

AMO Launches Next Generation Interceptor

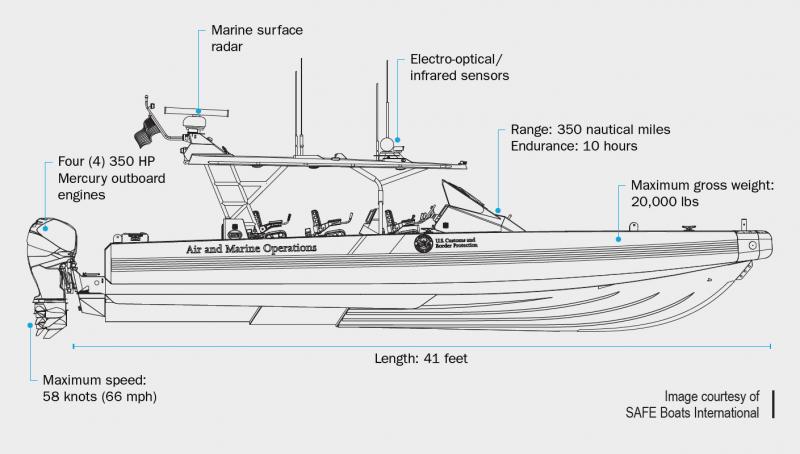

To enhance operations, AMO is planning to add at least 52 next generation interceptors to its arsenal of vessels. Through a contract with SAFE Boats International, the new interceptors will feature an advanced hull design, safety equipment and electronics, providing agents with a high level of protection, mobility reliability.

The vessels are designed to meet emerging Department of Homeland Security mission requirements and will be deployed to marine units nationwide, including Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, southeast Florida and San Diego. They will defend the nation’s coastal waterways combating smugglers and terrorists.

"We are excited to share this new vessel with our stakeholders, including those on Capitol Hill, within our department and the American public whom we serve and protect," said Randolph D. Alles, AMO’s former executive assistant commissioner.

Maintaining the Fleet

Bold, can-do attitude gets things done

By Paul Koscak, photos by Glenn Fawcett

Maintenance is key to the National Marine Training Center’s success, National Marine Training Center Director Martin "Marty" Wade notes. "You need world-class support when you have a world-class program."

World-class support takes place nearby at AMO’s huge National Marine Center, a maintenance facility that resembles an industrial park. Buildings for every specialty line both sides of the facility’s quarter-mile central roadway—a rigging shop, engine shop, fiberglass and vinyl shop, machine shop, paint shop, electronics shop, warehouse and parts department and administrative offices. Altogether, there’s more than 178,000 square feet of workspace staffed by 68 Global Maritek Systems technicians and four CBP managers. "There’s really not much that we can’t do here," proclaimed Doug Wagner, the center’s director, who began his career as an aircraft mechanic at just 17 when he entered the Air Force.

Walk into the cavernous rigging and electronics shop—the size of an airplane hangar—where a dozen interceptors on trailers are squeezed side by side, each undergoing some phase of refurbishment. The whines, grinds and rattles of power tools reverberate throughout the building as fiberglass cracks are sealed, electronic systems replaced, propulsion systems upgraded and engines are replaced or overhauled. A few vessels are Coast Guard retirements destined to join the CBP fleet. Even vessels from the West Coast are serviced at the facility, Wagner said.

Completed craft are many times stored in the maintenance facility’s depot for a quick swap with any marine location. Four semi-trailers are on hand ready to deliver.

By contrast, technicians in the electronics shop quietly sit by long workbenches testing, calibrating and fixing all manner of maritime navigation and communication gear. The machine shop also boasts vintage fabricating equipment—lathes, drill presses, milling machines—devices few marine maintenance shops have. The shop can manufacture difficult-to-replace parts or craft entirely new components.

In the fiberglass shop, Border Patrol SAFE boats are refitted with new collars, the component that gives the boat its name. "Our quality is superior," offered supervisor Lee Author. "Where a local marine shop would take three weeks, here we can do it in a week and at just a third of the cost."

As an example, Wagner produced a photograph of an electrical panel refitted by a marina. It showed a chaotic tangle of wires, some bunched with plastic zip ties. "This was a shock," he said, also pointing out the wrong gauge of wire in the mix. The second photo was almost unrecognizable after the facility’s electricians refitted the refit—orderly, clear tracks of properly secured wire taking up less than half the panel.

Under Wagner’s leadership, Global’s 165 technicians not only perform maintenance at St. Augustine but also at 28 other sites throughout the country, including Puerto Rico and St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. The company keeps up more than 300 craft along with vessels from the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers, National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Marine Corps, saving those agencies and the taxpayer considerable money. Global offers CBP access to the country’s largest parts inventory, on-site warranty work and up to 50 percent off retail part prices.

Another bargain is the customs automated maintenance inventory tracking system or CAMITS. The nation-wide system streamlines procedures, tracks purchases, records repairs, schedules required tasks and projects future maintenance, "and it’s not expensive," added James Warfield, supervisory marine interdiction agent and maintenance deputy director.

Can do

Still, the facility’s most powerful tool isn’t found on some shelf. It’s an attitude. "We ask, and they say yes," is how Wagner describes the technicians. "They will find a way to make it happen."

A crucial creation that keeps vessels from an early trip to the junkyard is an example of their ingenuity.

Over time, an engine’s vibration eventually weakens and breaks the transom, part of a vessel’s stern where the engine is bolted. Like any invention, the breakthrough took numerous trial-and-error and commitment that paid off in a refabricated transom made with certain composite materials that deaden vibration and strengthens the stern. "We invent things," Wagner said, who estimates the beefed-up transom saved the government $3 million and adds about five years to a vessel’s life.

That entrepreneurial mindset is noticed. In 2011, the facility received the Industry Leader Safety Award; in 2012, the commissioner’s Mission Integration Award and in 2013, the Small Business Achievement Award for innovation and cost savings.

Wagner credits the facility’s success to the staff’s sense of purpose. "They embrace our mission," he explained. Technicians take pride in their accomplishments, embrace innovations and are "eager to learn and work for the country and have a high work ethic. Many are former military."

Applicants seeking jobs at the maintenance facility learn from the first interview there’s a higher calling expected as important as exceptional skills.

"Everybody brought on board is told they’re not coming here just to maintain assets," Warfield added. "They’re not just contractors. They’re part of Homeland Security and the mission to protect the United States."