Natural Enemies

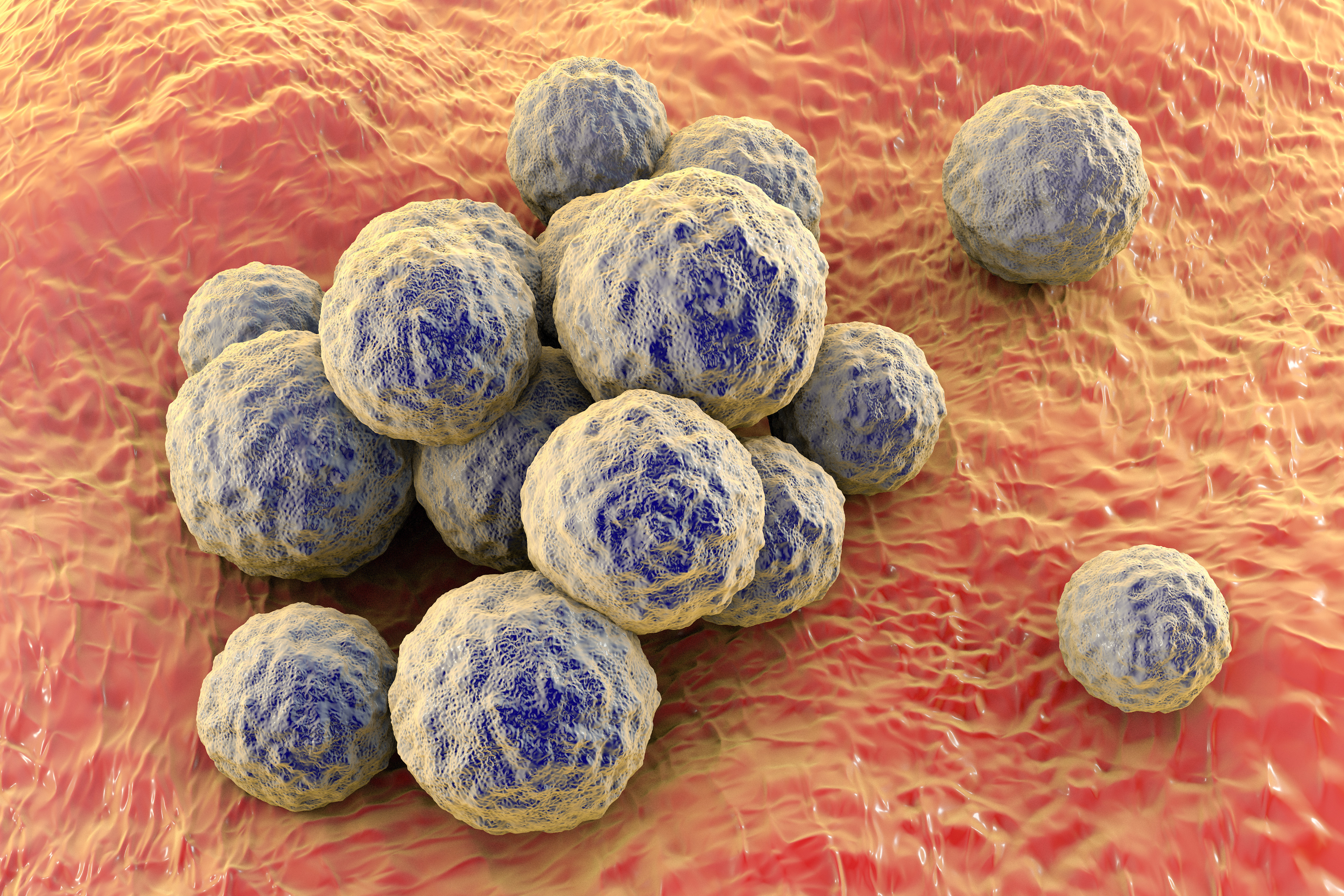

Bacteria methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a multidrug resistant bacteria (MRSA), on the surface of skin or mucous membrane, 3D illustration by Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

A middle-aged man arrived from Beijing at the Detroit Metro Airport on a hot, sunny day in May. The man told a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer that he was a professor in the United States whose specialty is molecular biology.

The officer referred the man and his baggage to a CBP agriculture specialist (CBPAS), who asked the professor if he carried any biological materials – specifically plasmids, which are small DNA molecules that can replicate independently, often used in the laboratory manipulation of genes.

The professor denied having any such materials, but after an X-ray and a physical inspection of the baggage, the CBPAS found a paper bag containing four vials of plasmids. When questioned about the vials, the professor became evasive, saying only that they were bacteria and that he had no paperwork or permits for bringing them into the country. He claimed a fellow researcher placed the vials in his suitcase, then admitted he often imports biological materials without declaring them.

Two of the vials were labeled “MRSA” -- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. MRSA is a contagious staph bacteria that is highly resistant to many antibiotics. In health care settings, such as hospitals and nursing homes, MRSA can cause pneumonia or sepsis, a life-threatening reaction to severe infection in the body. Anyone can get MRSA on their body from contact with an infected wound or by sharing personal items, such as towels or razors, which have touched infected skin. The risk increases when a person is in places that involve crowding, skin-to-skin contact, and shared equipment or supplies.

Follow-up emails to the professor’s employer revealed that the university neither knew nor approved of his transport of the vials, and that the materials they contained were outside the scope of his research. The case was turned over to the FBI and the vials were subsequently destroyed.

Science and medicine depend on the ability of researchers to transport physical specimens around the world. Some of these specimens are hand-carried onto aircraft, while others are shipped through cargo and international mail and express consignment pathways.

The vast majority of scientists and researchers obtain the proper permits to travel with biological materials. But what happens when people carry or ship dangerous substances into the United States without permission because they don’t want to deal with filling out the proper paperwork? Worse, what if someone smuggles in a substance with the specific intent of hurting people or damaging U.S. crops or livestock?

CBP trains its agriculture specialists to detect and intercept potentially harmful biological agents. A biohazard is typically a biological agent that can harm people. It can be a virus, bacteria, or a toxin produced by bacteria or an animal. “Biological agents can be more lethal than chemical weapons and more difficult to detect than nuclear weapons,” says Dr. Romelito Lapitan, Director of Agro/Bio-Terrorism Countermeasures for OFO’s Agriculture Programs and Trade Liaison (APTL).

A strict permitting process governs most organisms, cells and cultures, antibodies, vaccines and related substances, whether of plant or animal origin. Biological specimens of plant pests, in preservatives, or dried, may be imported without restriction, but are subject to inspection upon arrival in the United States. This is done to confirm the nature of the material and to make sure it is not viable if it happened to be released either accidentally or deliberately.

CBPAS give passenger baggage and cargo extra scrutiny for pests, plant pathogens, and prohibited animal products if the baggage and cargo have originated in countries known to be at high risk for those pests, pathogens, and products.

CBP officers also pay attention to the appearance – in terms of physical health – of travelers arriving from parts of the world where there have been outbreaks of contagions such as Ebola and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). From 2013-2016, more than 11,300 people died from Ebola in West Africa. More than 8,000 people were infected with SARS worldwide after its initial outbreak in Hong Kong in 2003; more than 800 died.

“CBP officers on the front lines act as a force multiplier as we work to protect the nation from infectious disease threats linked to travel,” explains Dr. Francisco Alvarado-Ramy, Chief Medical Officer for the Quarantine and Border Health Services of the Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Dr. Alvarado-Ramy, who is also a Captain in the U.S. Public Health Service, recalled “two instances when CBP officers were able to prompt international travelers, who originally were not truthful about their health status, to disclose that they had tuberculosis. Another traveler was stopped trying to bring bacteria, without a permit, that can cause acute gastroenteritis.”

Nothing new

Biological warfare has long been a staple in book and movie thrillers. Authors ranging from Jack London in the 19th century to Tom Clancy and Stephen King all imagined scenarios in which evildoers use viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens as weapons to control or annihilate people – either outright or by poisoning their water, crops, or livestock.

The word “bioterrorism” might conjure up images of cutting-edge industrial-scale laboratories producing undetectable toxins that can kill millions in a matter of days. But threatening people with biological agents is as old as humanity itself, and humans have proven remarkably inventive in harnessing the lethal potential of nature.

Thirteen hundred years B.C., the Hittites, an ancient Middle Eastern empire stretching from northern Turkey into Iraq and Syria, sent diseased rams – possibly infected with a devastating bacterial agent called tularaemia – into cities they wanted to conquer. In 204 BC, Hannibal ordered his Roman soldiers to toss clay pots filled with venomous snakes onto the decks of his enemies’ ships.

A thousand years later, medieval armies catapulted diseased cadavers into besieged cities. In 1763, during the French and Indian War, British soldiers at Fort Pitt sent “gifts” of blankets bearing smallpox in an attempt to wipe out indigenous tribes who had no resistance to the disease. American Civil War soldiers placed dead animals into ponds to taint drinking water.

Today, terrorists can grow a wide variety of harmful biological agents that can include viruses, bacteria, toxins, and even fungi. Furthermore, these “natural” organisms can be re-engineered or altered to make them more resistant to medicines or other treatments, or easier to disseminate into the environment.

In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued an interim “consensus report” resulting from a study commissioned by the Department of Defense. The report warned that advances in biotechnology and, more specifically, synthetic biology are creating opportunities for terrorists and other “bad actors” to weaponize pathogens and other bio-agents.

In the final report, published in June 2018, the Academies concluded that the government should focus on the ability of terrorists to recreate known pathogenic viruses and making existing bacteria more dangerous.

The CDC classifies biological agents that could be used for bioterrorism in three categories, depending on properties such as availability, ease of production and dissemination, and potential mortality rates.

Natural biological agents appeal to terrorists because they are easy and relatively inexpensive to obtain or develop, difficult to detect, and an effective way to generate panic and widespread fear.

But synthetics are also dangerous. In the same study, NASEM warned that terrorists could resurrect diseases that have been eliminated – such as smallpox and polio – and conceivably make them even deadlier through gene or genome editing.

Although rapid advances in gene and genome editing are benefiting people suffering from a broad array of illnesses, terrorists could just as easily use this technology to turn a virus into a weapon of mass destruction, according to Microsoft founder Bill Gates. Gates’ charitable foundation is funding research into spotting disease outbreaks and speeding up the production of vaccines.

Speaking at a security conference in Munich in February 2017, Gates cautioned international leaders that the world’s next deadly pandemic “could originate on the computer screen of a terrorist.”

The threat has the attention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). “Biohazards are special,” says Supervisory Special Agent (SSA) Edward H. You. “They are open source, widely disseminated, and unregulated, so they are difficult to detect. We need to enlist academics, public health officials, scientists, and universities to be the guardians of science.”

The FBI has launched a new campaign called “Safeguarding Science.” SSA You explains that the campaign’s goal is “to build a cadre of ‘white hats’ to work with law enforcement on this issue. We are in the midst of a biological space race, but we just haven’t had that ‘Sputnik moment.’ Yet.”

CBP’s Dr. Lapitan agrees: “Microbes can be weaponized. Someone could synthesize an organism to make it more virulent, then when you analyze it and try to find it in any existing databases, it’s unknown. So then it is more difficult to come up with countermeasures to combat it.”

Plant evidence

The same techniques could also be applied to plants. Dr. Lapitan notes that cross-breeding certain types of plants could conceivably make a plant more invasive and therefore more destructive to crops or native flora.

Nevertheless, the vast majority of deadly or dangerous biological material that crosses the border into the United States is not intended to cause harm. Rather, it is essential to legitimate scientific and medical research.

“Bringing biological samples into the United States can be indispensable in certain research areas,” according to Dr. Alvarado-Ramy. “There are times when U.S. scientists need biological specimens in order to carry out their work. That work is critical to continue bringing better diagnostic tests, treatments, and ways to prevent disease. Americans rely heavily on the information produced by these scientists.”

But there are rules for importation of those materials.

In January, for example, at an express consignment facility near Chicago, a CBPAS inspected a shipment manifested as “harmless biological samples.” The shipment, destined for a plant pathology research lab in the midwest, was a live rose plant, complete with roots and soil.

The parcel contained a permit issued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) for transporting live plants, noxious weeds, and soil – and, specifically, for the select agent called Ralstonia solanacearum. But the required APHIS/CDC Form 2 was not included.

That might seem like a minor infraction, but Ralstonia solanacearum is a lethal pathogenic bacteria that causes a plant disease called “bacterial wilt.” This disease could cost millions of dollars to eradicate if introduced into the United States. This soil-borne bacterium attacks nearly 200 plant species, including key crops like potato, tomato, cotton, and soybeans.

After some deliberation, the USDA decided that the shipment could enter – this time. However, because the importer had done this once before, the USDA sent a letter warning them that future violative shipments would be refused entry, and instructed them to provide the USDA with a list of steps they plan to take to make sure this does not reoccur.

The CBPAS who intercepted this particular sample, Dragan Muvceski, immediately safeguarded the shipment by placing it under quarantine in the CBP agriculture lab at the express consignment facility until he and his colleagues could research the plant material.

Muvceski said he then recalled learning about Ralstonia solanacearum (or bacterial wilt) in a plant pathology course at Purdue University. “I still vividly recall the professor stressing how dangerous and destructive this disease is,” said Muvceski, a 2004 graduate of Purdue University in Indiana. “Infected land can sometimes not be used for crop growth for many years, as the soil-borne pathogen lies dormant for a long time.”

Muvceski spent summers on his grandmother’s farm in rural Macedonia where his father was born. “It was there I learned the importance of healthy plants and animals and what agriculture means to us as humans.”

Muvceski’s supervisor, Supervisory CBPAS Lin-Mai Malmstrom, shares his passion for the job – and the natural world. “I’ve always been fascinated with plants,” Malmstrom said. “When I was growing up in Taiwan, I would often accompany my dad, foraging for edible plants such as fiddlehead ferns, mushrooms and other plants that I only know by their Taiwanese names.”

She noted that if CBP agriculture specialists did not intercept pests, plant diseases, invasive weed seeds, and prohibited animal products, U.S. agriculture would suffer, resulting in production losses and higher prices.

“Whether the work of a person with nefarious intent or result of natural evolution, the biological threat is incessant and clever,” says Dr. Alvarado-Ramy. “Anyone who lived through the anthrax letters in 2001 knows the terror that such attacks can instill.”

Powerful partnerships

CBP may be on the front line of preventing dangerous materials from entering the United States, but it is not alone in this fight. CBP is supported by other agencies across the federal government.

DHS’ Office of Health Affairs (OHA) is responsible for preparing for emergencies that affect the health of Americans. Currently, OHA’s BioWatch program distributes collection devices to 30 high-risk areas throughout the country to detect the presence of aerosolized biological agents before they generate symptoms in the populace.

In addition, DHS’ Science and Technology (S&T) Directorate plays a role, having developed methods for analyzing suspicious powders and other substances. S&T also tests the accuracy of commercially available systems used by first responders to render harmful substances ineffective. More recently, S&T launched a Center of Excellence on Cross-Border Threat Screening and Supply Chain Defense. The Center provides research support; develops solutions, protocols, and capabilities; and enhances the ability of DHS and its partners to detect, assess, and respond to biological threats and hazards.

The CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine works with airlines and cruise ship operators to identify sick travelers and notify other passengers of their potential exposure.

The division operates Quarantine Stations at 20 U.S. ports of entry – primarily airports – where most international travelers arrive. These “Q stations” connect with state and local health departments as well as with ministries of health in various foreign countries.

USDA-APHIS animal health officials have identified “high consequence” foreign animal diseases and pests that do not currently exist in the U.S. These diseases and pests, if introduced, pose a severe threat to U.S. animal health and – in some cases – could jeopardize the U.S. economy and human health.

“These threats are real,” says Dr. Elizabeth Lautner, Associate Deputy Administrator, Diagnostics and Biologics, Veterinary Services, USDA-APHIS.

Some of the most significant threats are African swine fever (ASF), classical swine fever, foot and mouth disease, avian influenza (highly pathogenic or of zoonotic significance) and virulent Newcastle disease.

In early August of 2018, the USDA alerted CBP to the first-ever detection of ASF in China. “ASF is a foreign animal disease that has never been detected in swine in the United States,” says Lautner. “It is a highly contagious disease that can have mortality rates as high as 100 percent.”

The USDA quickly alerted CBP and asked the agency to apply extra scrutiny to passenger baggage from any country affected by ASF just to make sure that all pork products – which are inadmissible without the proper permits – are handled and disposed of appropriately.

Newcastle disease, meanwhile, is a highly contagious, fatal bird virus that affects many domestic and wild bird species. It is spread by direct contact among birds through coughing and sneezing, and through fecal droppings. People can spread the disease by moving infected birds, moving equipment and feed, and by transferring the virus on their clothing and shoes.

During the 1970s, a major outbreak in California forced poultry farmers to euthanize nearly 12 million birds, costing taxpayers $56 million and driving up poultry prices for consumers. In 2003, the disease reemerged, killing another three million birds and costing $161 million.

Since May 2018, 34,000 so-called “backyard birds” have been euthanized in southern California alone. “Currently, APHIS is working with the state of California to eradicate Newcastle disease in backyard birds and to prevent its entry into commercial poultry production,” says Dr. Lautner.

Finally, state and local agencies are also on the front lines of this fight. The role of first responders is key; in the summer of 2018, the state of New York wrapped up its sixth annual large-scale emergency response training exercise, bringing together hundreds of police and first-responders to familiarize themselves with techniques and best practices to prepare for and respond to all kinds of attacks, including bioterrorism.

For CBP, these partnerships are key, especially with the volumes of travel and trade crossing the border every day. “Despite all the training, we don’t have enough staffing resources to inspect everything and everyone, 100 percent,” says CBP’s Dr. Lapitan. “All we can do is manage the risk, and to do that effectively, we must know the threat.”