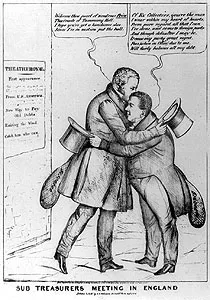

greeting a fellow embezzler in London.

It was a scandal of stunning proportion. Investigated by the House of Representatives in 1839, with the conclusions published as "The Defalcations of Samuel Swartwout and Others"-meaning embezzlements-the story exposed the widespread misappropriation of funds intended for federal coffers. The missing money remained unnoticed until the close of 1838, when Swartwout stood accused of carrying out the largest individual theft in the history of CBP's legacy Customs service.

According to the congressional inquiry, Swartwout absconded with $1,225,705.69 in public funds and fled to London. That translates to roughly $30 million in year 2011 dollars-a shocking sum by any standard.

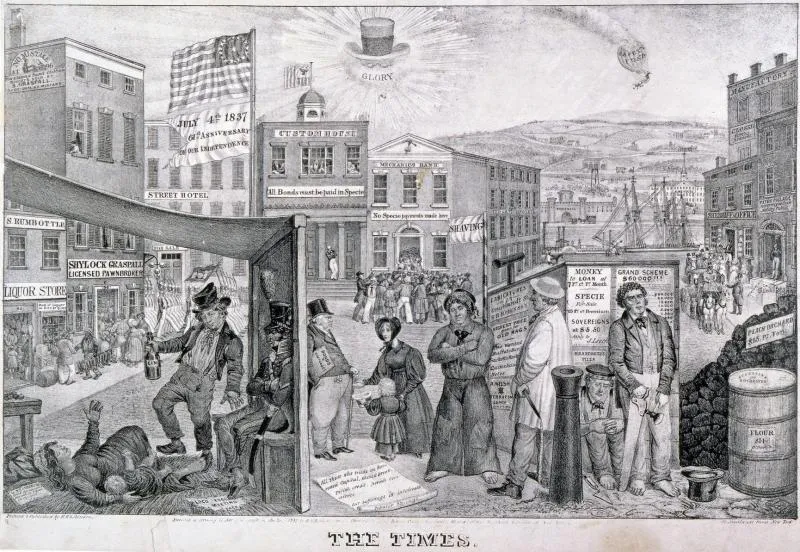

President Andrew Jackson rewarded his staunch supporter, Samuel Swartwout, with two consecutive appointments as collector of customs at New York, where he served from 1829 through 1837. The collector was in a position to acquire and transfer substantial amounts of money. While collectors at all ports typically brought home more money than their pay scale indicated, customs collector for New York was the plum posting. The port of New York operation was the moneymaker for the still-young nation; the customhouse annually contributed one-half to two-thirds of the entire U.S. Treasury's funds-the nation's bankroll-through collection of duties on trade goods.

Cedar Street in the Panic of 1837

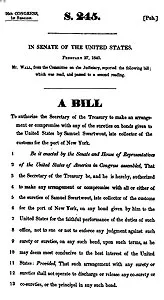

The Treasury tacitly permitted withholding of funds by collectors during their service. Unlike today, customs collectors were personally liable for assessments of bonds and, if sued, had to pay any judgments against them. Collectors could request Treasury support to settle the awards, but in practice they found it easier to stockpile customs money to cover these potential personal debts. Swartwout reported $221,907.36 to the Treasury (worth approximately $5 million in year 2011 dollars) that he retained until his last quarter of service, when the government expected him to return the money.

Swartwout accounts, 1840.

As illustrated in the Swartwout case, checks and balances designed to account for all funds failed. The naval officer assigned to verify transactions didn't do his job. The comptrollers and auditors disregarded theirs. Clerks who knew that Swartwout took some money for private purposes didn't report it-they believed they worked for Swartwout and owed their allegiance to him, not the U.S. government; after all, he had the power to hire and fire them. Swartwout adamantly maintained that someone falsified records after his departure to make it appear he committed massive fraud.

After the hubbub over Swartwout, what was the outcome? In practice, little changed. Friends of politicians in power still benefited for decades until the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 replaced the old patronage system of filling offices with one based on merit. The Treasury never recovered the purported "defalcated" monies, though Swartwout forfeited some of his American property under a compromise agreement. Assured he would not face charges for embezzlement, Samuel Swartwout returned to the U.S. He died in New York in 1856.

What about U.S. Customs and Border Protection history would you like to know? Contact us at CBPHistory@dhs.gov.