sugar and molasses import and

consumption values. Photo

Credit: David Rumsey Map

Collection, www.davidrumsey.com

All sugar is not created equal. Cane and beet sugars and their related products contain different degrees of sweetness depending upon where and how they are grown. Harvesting and processing raw sugar added impurities like bits of cane among the crystals.

Salt water contamination could be introduced during transport across the ocean. Beginning in the Colonial era, when sugar became a major American import, these and other factors had to be considered and played a role in duties assessed. Guidelines for customs examiners gave detailed instructions on how to account for such elements.

instruments like this half shade polariscope,

patented in 1907, for at least sixty years

in sugar analysis. Accuracy was critical.

Small degrees of difference in the samples

translated to substantial overall duties

assessed across a whole shipment.

Photo Credit:U.S. Customs and Border

Protection historical collections

Through the early 1800s, evaluating sugar was done by eye in comparing color. Weight was another factor, with the assumption that heavier meant sweeter sugar that was subject to higher tariffs. But these methods of analysis were too subjective and inconsistent-and left the process open to fraud and corruption. Sugar could be artificially colored, for example, to make a higher quality product appear to be a darker lower grade, thus saving duties and costing the United States Treasury vast sums of money. U.S. sugar producers and refiners complained that the value of their products was undermined by faulty import assessments.

To combat these problems, the United States government oversaw many efforts to make the evaluation of sugar more objective and scientific. In the 1840s, medical doctors and pharmacists were added to appraisal teams to test Caribbean molasses using hydrometers that measured specific gravity.

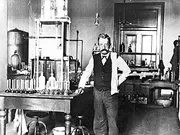

sugar at the New Orleans laboratory, 1906.

The flasks on the left contained sugar in

solution, while the ones on the right

incorporated a small amount of lead

acetate to determine impurities.

Photo Credit:U.S. Customs and Border

Protection historical collections

A series of regulations were passed. The Act of June 30, 1864 provided for the use of Dutch standards for assessment of duty on sugar, where color was verified by chemical or mechanical means. Use of the optical polariscope to determine actual sugar strength was initiated in 1883. The Tariff Act of July 24, 1894 made testing necessary, and the polariscope (along with a specialized version called a saccharimeter) became standard equipment.

It took years to work out basic issues surrounding sugar analysis.

using a half shade polariscope to examine

a sugar sample, 1968. The cylindrical

apparatus on the right is the light source.

Polarisopes were replaced by automatic

polarimeters in the 1970s.

Photo Credit:U.S. Customs and Border

Protection historical collections

There were many variables to contend with, including such factors as the quality of light used with the polariscope, the quantity and selection of samples, accounting for errors introduced by preparing samples for study, and reading the test results. As accuracy and consistency became possible-and then required-the need for trained examiners prompted the advance of laboratories and customs chemists. A study by experts including Frederick Bates and W.A. Noyes of the U.S. Treasury's Bureau of Standards resulted in new procedures in 1908, and led to standardization of testing methods and perfection of lab equipment including the polariscope, sugar tube, sugar balance, and glassware.

The early polariscopes were still in use as of the 1970s, even as processes for sugar analysis continued to be explored and revised. Efforts to eliminate toxic elements like lead acetate used in producing samples for testing, for example, were introduced by the late twentieth century. Today, the technology is more advanced-digital polarimeters have supplanted mechanical polariscopes-but the basic premise is still the same. Trained chemists and lab personnel are needed to prepare the samples, conduct the tests and verify the results. And polarization remains a tried and true measure of sizing up sweetness for United States Customs and Border Protection.